STAMFORD — Stamford resident Anthony Venezio said he thought about writing his will when he was drafted for the Vietnam War.

He was 20 years-old when he took the train to New Haven to begin his service in the U.S. Army May 1971.

However, he said he considered his time in the Army a personal "awakening” that prepared him for his eventual civilian job. It’s also an experience that resulted in him being named the grand marshal for Stamford’s Memorial Day Parade, held last weekend.

Venezio completed his basic training at Fort Dix, N. J. However, he developed stress fractures in his legs, which a doctor said meant he could never be an infantryman.

He was then assigned to the 5th Army Headquarters and sent to Fort Polk, La., now known as Fort Johnson, where he trained to distribute orders to individuals and units.

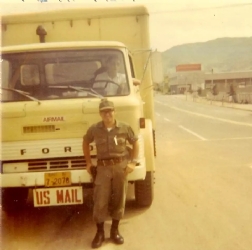

Venezio served in the 8th Army Korean Support Command and was stationed at the 1st AG Military Mail Terminal in Incheon, Korea. He guarded mail delivery trucks that delivered letters and packages across Korea and would eventually get to United States soldiers in Vietnam.

Those trucks started their runs as far north as Incheon, 74 miles from North Korea, made stops at military bases and went as far south as the city of Busan, which sits on the southeastern corner of the Korean peninsula.

Venezio said making sure soldiers could get those letters was "totally important” during a war.

"You feel you're still attached to somebody over there, you know you're not isolated,” Venezio said. "There's still people who care for you and are concerned about you.”

He was then promoted and scheduled other soldiers to go on the mail runs he once made. At one point, he put down what he said was a "mutiny."

U.S. Army soldiers and Republic of Korea Army soldiers worked together under Venezio to load and unload trucks and organize mail. However, some of the United States soldiers were "just slacking off,” Venezio said, and the Korean soldiers had enough and "went on a strike” in response.

To help resolve the conflict, Venezio scolded the American soldiers for their behavior and convinced the Korean soldiers to return to work.

"As an (non-commissioned officer), you had to get other people to work for you, which takes a little psychological thinking,” Venezio said.

Venezio called the experience in the service an "awakening” and said he fell in love with the country where he met his wife, Un Cha.

"It really made me grow up,” Venezio said. "You have to do everything yourself and you had to become self-sufficient.”

He left Korea in December 1972 to return home and saw for himself the antiwar sentiment that had swept the country. He said there were protestors at the Army Base he stayed at in Oakland, Calif. when he came back to the states before he left for Stamford. He was a sergeant when he was discharged.

"It was depressing,” Venezio said. "You had to be careful sometimes, where, if you wore your uniform or anything, because people would treat you badly.”

He also returned with his wife and was expecting their first child. His old job didn’t pay enough, though, he said, so he took a position in the post office that used to stand on Atlantic Street, where he worked his way up to a supervisor role.

The mail processing system became more automated, though, so Venezio learned how to work and repair those machines and became a maintenance supervisor.

He credited his time in the Army for giving him the skills he needed to succeed at his job in the post office. He retired in 2006.

Venezio said it always made him proud to have served his country.

"I followed, even though it wasn't intentional, in my father's footsteps, even went to Korea like he did,” Venezio said.

His father served during World War II and was a part of the United States military contingent that occupied South Korea after the war.

Venezio now serves as a trustee for the VFW Post 9617, which gave him "a sense of meaning again,” especially being around others who also took an oath to preserve the United States Constitution. He’s been a part of the group for almost 20 years.

People who work in the post office also have to swear an oath to the Constitution, Venezio said. When a manager wasn’t around to give it to new hires, Venezio would be called upon.

"I still hold that seriously,” Venezio said. "They say that that oath you take never ends when you're in the military.”